Get back to the roots of our varied food heritage

Fife’s food has for many centuries been bonded to both land and sea through international trade, fishing and agriculture, and all three industries still play a major role in the region’s prosperity.

There are ancient seafaring links to northern Europe, fertile farmland rolls from one end of Fife to the other, and there is UK and international demand for the high quality shellfish landed by the Kingdom’s Pittenweem-based fishing fleet.

Generations of producers of cereals, vegetables, livestock, soft fruit and seafood have provided a wonderful base for a food sector prepared to adapt and grow.

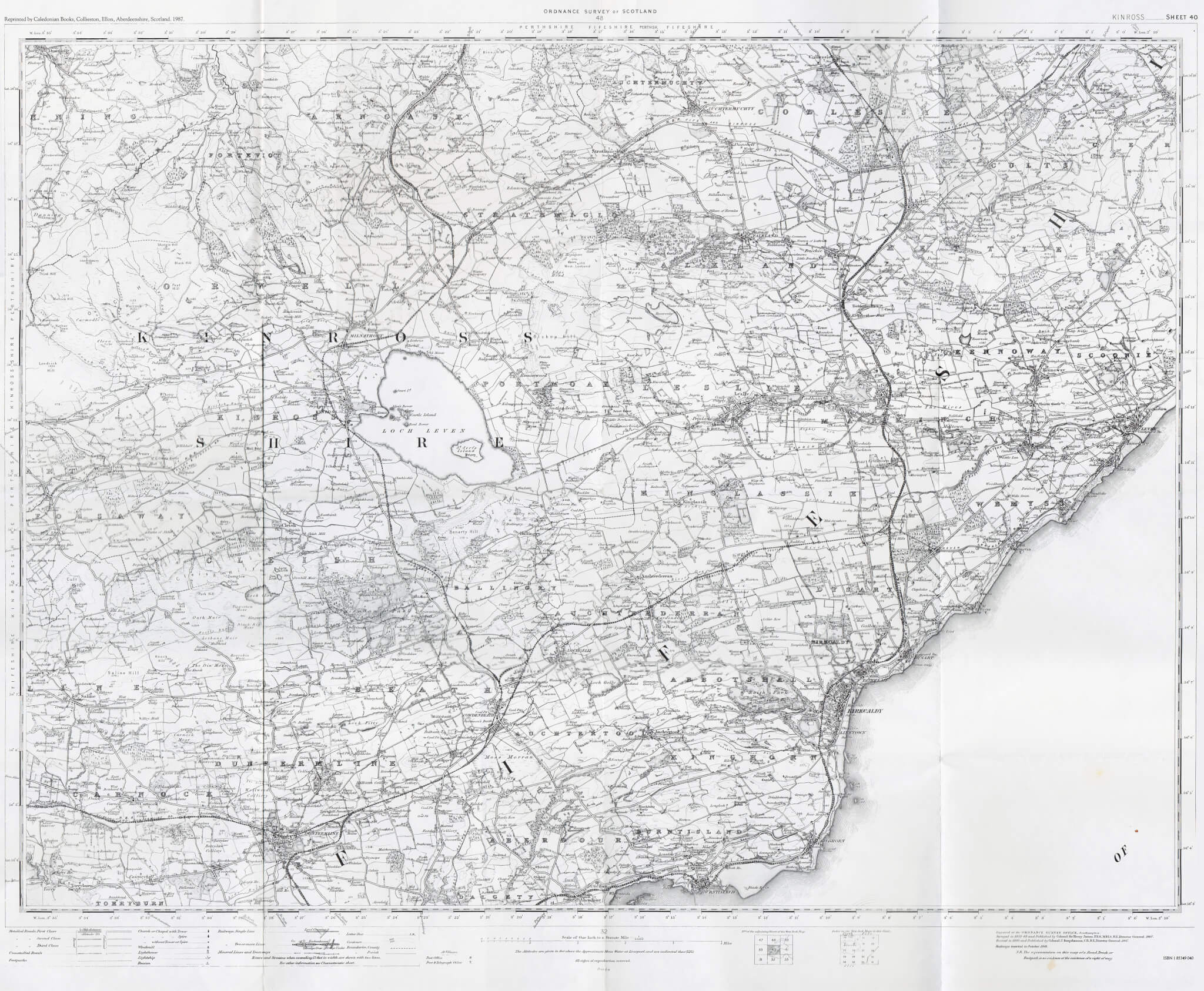

Historic Maps

In this section we will show parts of the Kingdom as they have been mapped and recorded for hundreds of years. The names of many communities, farms and estates have endured since records began.

Facts & Figures

Some of the statistics behind food production in Fife make interesting reading, and reflect the constant change that has led to modern farming and fishing methods and employment trends.

Fife’s agriculture, fishing and drinks industries bring many millions of pounds to the local economy, and provide several thousand jobs.

There are over 1500 agricultural holdings catering for cereals, general cropping, horticulture, specialist pigs and poultry, dairy herds, cattle and sheep, deer, and specialist grass and forage. They employ over three thousand people, and most of the jobs are full-time.

Scottish Sea Fisheries statistics (published September 2012) show that Pittenweem had 1401 tonnes of landings worth just over £4.5 million in 2011, with prawns making up the bulk of the catches. Other species included edible crabs, lobsters, razor fish, scallops, squid, surf clams and velvet crabs. There were 120 active Pittenweem district fishing vessels in 2011, and they provided employment for 165 fishermen, 51 of them part-time.

Food Fact

A very early seafood product from the East Neuk was the “Crail Capon” – a sun dried haddock. The capon is represented in the town’s unique weathervane, which has a fish as part of its design. It is thought that fish was exported from Crail as early as the 9th century. At one time the Royal Burgh of Crail had the largest medieval market place in Europe.

Food Fact

In the 13th century the Firth of Forth’s native oyster fishery was one of the most commercially important in Scotland. At its peak it provided 30 million oysters per year, which were exported to Glasgow, western Scotland , England and the Continent. The trade died out completely in 1920. Although it was thought that Firth of Forth oysters had become extinct, live specimens were discovered by scientists from the University of Stirling in 2009.

Food Fact

Anstruther was Scotland’s main herring fishing port. A permanent reminder of the trade is the Anstruther – based Reaper, a two masted Fife herring drifter which was built in 1902, and now belongs to the Scottish Fisheries Museum, www.scotfishmuseum.org.

Food Fact

The Newburgh Orchard Group (www.newburghorchards.org.uk) holds special markets every year, mainly to sell plums and apples grown in and around the town. In one bumper year recently 3000lbs of fruit and 600 jars of jam were sold. The area’s connection to organised fruit growing dates back to 1191, when Lindores Abbey was founded by monks from France. Their fruit was eaten locally, supplied to the Scottish royal court at Falkland, and made into alcohol. A 2003 survey looked at over 800 trees in nearly 70 locations, and found a number of varieties of pears, plums and apples.

Food Fact

Lindores Abbey near Newburgh is said to be the oldest recorded distilling site in Scotland. A monk at Lindores, John Cor, was distilling as far back as 1494, and in the same year King James IV of Scotland, through the Royal Scottish Court at Falkland, granted the monk “eight bols of malt” to make whisky. The abbey was supplied with spring water from nearby Ormiston Hill via Monks Well and Abbots Well (source www.thewhiskybarrel.com). In 2017, a Lindores Abbey Distillery starting distilling on this site once more.

Food Fact

Quaker Oats have been produced on the Cupar site since 1947. The site is currently home to Quaker Oats and Scott’s Porage Oats. It also produces Oat So Simple, as well as Quaker’s latest innovation, Quaker Oat So Simple Pots, designed to make porridge preparations even easier.

Food Fact

In 1973, the first commercial deer farm in Europe was established at Auchtermuchty in Fife. In 2016 Fife farmers Bob and Jane Prentice of Downfield Farm, Cupar established a specialist venison abattoir. It also has a butchery and a packaging plant.

Food Fact

Trials for the world’s first clear water, clean energy, sustainable king prawn farm took place in Fife by Great British Prawns Ltd. They launched their first commercial farm in Stirlingshire in 2019 and retain a presence in Fife.

Drink Production

Diageo to Daftmill – Massive to Micro

Fife is home to the 150-acre Banbeath site owned by drinks producing giant Diageo at Leven, where it packages white spirits, ready-to-drink products, and Scotch malt whiskies, and the scale of operations results in some astonishing statistics. There is near continuous bottling of Smirnoff vodka and Gordon’s Gin, at the rate of around 500 bottles a minute. 1400 different products are produced at the Leven site, and are shipped off to 180 countries. There are around 200 million litres of alcohol on site at any one time. Diageo also runs Cameron Bridge Distillery near Leven, where 100 million litres of spirits are produced every year. They include grain whisky, Smirnoff, Gordon’s Gin and Tanqueray.

More recently, Fife has seen increased developments at the craft end of the scale with Kingsbarns Distillery near Cambo opening its doors in 2014. With its first bottlings of whisky now available, the beautifully repurposed farm steadings house a visitor centre and charming gin rooms.

In addition Eden Mill Brewery & Distillery developed Scotland’s first single-site distillery and brewery in Guardbridge, making gin, whisky and beer. Eden Mill spirit is created in copper pot-stills and exhibits a wide range of flavours from botanicals sourced from the local area, as well as from around the world.

In 2017, the latest addition to Fife’s distilling scene, Lindores Abbey Distillery, opened its doors. With Lindores Abbey’s widely recognised links to the earliest written reference to Scotch whisky, the team there have revived a tradition dating back to 1494. After a break of 523 years, spirit is once again flowing from the copper stills at Lindores Abbey.

Other flavours are also coming to the fore in the region’s distilling scene. Lundin Distilling uses locally foraged gorse to create a classic London style dry gin. They’re adding other drinks to their portfolio too.

In the north of Fife, Tayport Distillery produces spirits and liqueurs with local, hand collected Scottish grains and fruit. The team there mill and mash the grain to produce their own base spirit. The distillery is now open for tours.

History of Brewing in the St Andrews Area

Fife’s brewing scene has experienced something of a renaissance in recent years.

St Andrews Brewing Company was founded in 2012, over 100 years after the last St Andrews brewery closed down. They were keen to re-establish St Andrews’ place among the great centres of Scottish brewing; with a focus on the area’s great clean water, heritage malts and local ingredients. Their two St Andrews pubs are an ideal place to taste the range of beers and brewery tours are also available.

Located in the very same spot that once housed the legendary Seggie Distillery, founded by the Haig Brothers in 1810, Eden Mill opened its doors on the site of the former Guardbridge Paper Mill. It’s particularly known for its range of gins but it started life as a brewery in 2012. The craft beer and IPA range celebrate a wide variety of styles from a Belgian-inspired wheat beer to a unique spiced porter, a classic hop-heavy IPA to a gentle and fruity golden ale. The team draw upon their distilling skills to flavour special editions in bourbon and whisky barrels too.

In the East Neuk of Fife, craft breweries are also seeing a resurgence with the organic Futtle, based at Bowhouse near St Monans creating farmhouse beers and serving an eclectic range of beers, cocktails and whiskies at their tap room. They’re also using locally foraged seaweed to add to the drinks.

Ovenstone 109 is one of the newest additions to Fife’s brewing scene. It produced its first beers in 2018 at its brewery near Anstruther. Started by engineer, Nick Fleming, Ovenstone 109 has set out to make great tasting, unique, craft beers; but with a focus on a sustainable approach that benefits the planet and the local community. His world-class engineering firm built many things, including the system that recovered rocket fuel from the Space Shuttle solid rocket boosters, and this microbrewery uses slick technology to create delicious beer.

Yesterday's Diet

The Fife Fishermen’s Diet

Contributed by Jen Gordon, Scottish Fisheries Museum

When it comes to the history of “what people did”, it’s very easy to generalise and to make assumptions.

Often, when it comes to the daily habits of our ancestors we have very little evidence to go on.

Fishermen would keep logbooks of catches and landings and conditions at sea but not so much about what they ate on board.

My great grandfather was the skipper of a steam drifter and my granny remembered he drank tea so thick with sugar that the spoon stood upright in the cup – but who’s to say the rest of his crew had the same sweet tooth?

All we can do is look at what foods were available then, eke out what details we can from receipt books, listen to the memories of those that were there, and guess at what dishes were prepared from the basic and nourishing staples that would have kept these hardy men going in what is surely one of the most dangerous jobs done by man.

Many fishermen started life on board as cooks when they were in their early teens. They have vivid memories of the colossal task of feeding a hungry crew of elders, with only basic facilities in a tiny galley, while the boat rocked back and forth in the high seas! Peter Smith, the fisherman – poet of Cellardyke, recalls in The Fishermen’s Pride:

“Then comes ‘O’, “Olive Leaf”, Losh! I canna miss it.

In the auld ane I gaed wi’ my first scum net;

We had nae graun galley a’ fixed up wi’ care,

We cookit in the bunk, and spewed in the flaer.

Roon the Girdleness Pint wi’ a southerly hash,

Me in the forehould wi’ ma dishes tae wash;

… I’m sure Willie Smith kens a difference noo,

When he minds o’ the stuff I made something like glue.”

Later, when the old sailing “Olive Leaf” was replaced by a steam powered vessel of the same name, with improvements to cooking facilities, Peter recalled:

“But a’thing’s first-class noo in this “Olive Leaf”,

They had pies made in ashets, and stew, and roast beef.”

In her book The Skipper’s Notebook, Mary Murray cites the shopping list for the local butcher as evidence of what was consumed on her father’s boat when it went to the line fishing (a 10 to 12 day trip) – as you can see the crew ate very well indeed –

2 x 5lbs roast beef, 2 x 5lbs stewing steak, 2x 5lbs frying steak, 2 x 3lbs mince, 2 x 5lbs boiling beef, 3 x 5lbs link sausages, 20lbs sliced bacon or ham and 50 slices sausage meat.

For short journeys, when fishing from home rather than a distant port, individual crew -members would bring provisions in their “kit”. Syrup, treacle and tinned milk became increasingly popular into the twentieth century. Jessie Corstorphine of Cellardyke remembered an enamel butter cooler, steak, ham and egg going into her male relatives’ kits. She also remembered that when fishing away at Yarmouth – everyone would meet at the house where the skipper was staying for the weekly finances to be divvied up and there would be big “8d” pies and lemonade (or whisky!). Sometimes bits of the pie would go home to other family members wrapped in big hankies.

When we talk about the “Fife Fishermen’s Diet” we probably mean the traditional diet of all Scottish fisherfolk over the past few hundred years up until the 1960s and 70s when the diets of everyone in Fife and beyond were revolutionised with the ascent (and gradual descent in price) of ‘convenience’ foods heralded by the arrival of the famous fish finger!

Up and down the coast over the course of the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, oatmeal, potatoes, salt herring and white fish formed the basis of the fisherman’s diet. Butter, crowdie and eggs could be bought, or bartered for, from local farms.

In a very sustainable arrangement, a glut of dairy product could be swapped for a glut of seafood. A skipper might sell the most marketable portion of his catch, but would keep fish that were too big or too small for market, or the less commercial species found in the by-catch.

Once his family was fed, any outstanding supply of fish could be preserved for leaner times with a variety of cottage industry-style preservation methods – many families kept a barrel of pickled herring and white fish could be dried or smoked. The traditional smoked haddocks of the east coast of Scotland are still popular in the form of ‘Finnan Haddies’ or ‘Arbroath Smokies’.

A hake was a triangular wooden object specially made to dry fish on. The fish would take a day or two to dry and then would keep for a week after which they were boiled or roasted on a brander at the range. Alternatively (and seen more in the north of Scotland than in Fife) cod would be split and left to dry on stones on the shore – this process was, however, subject to spoilage courtesy of wet weather and peckish gulls!

Fluke (or flounders) and whiting were considered to be delicious. Rock turbot was only pleasant in early spring. Gurnards weren’t eaten as they were difficult to clean. Shellfish weren’t massively popular (mussels were seen largely as hook bait) though cockles and whelks were nibbled on – particularly by children playing on the beach – they could be cooked in a homemade ‘tinny’. Mackerel was considered “unclean” owing to the mistaken believe that they scavenged the flesh from decomposing bodies.

Simple recipes would be passed down from mother to daughter (and indeed son if a boat’s cook he was intended to be) – fancy cookbooks weren’t as popular as they are now. Fisher families ate a lot of broth (or kail) with potatoes, turnips and onions from local farms, sometimes based on a fish stock, sometimes flavoured with beef or a ham hock. Kale from the kale-yard provided greens (in some villages butcher’s shops sometimes had cabbage patches) and the soup could be thickened with peas or grains like oats or barley.

Women in fisher families, like their counterparts in agricultural communities, were often accomplished bakers making fresh batches of scones and oatcakes daily on the griddle before ovens became commonplace.

Plum duffs and clootie dumplings were often found to be bubbling away on the stove in both the galley and the fisherman’s home. Before the rise in popularity of the electric oven, oatmeal bannocks were baked at home rather than bread which came from the bakeries but which would quickly go stale on board.

An alternative to bread were the ‘Boat’s Biscuits’ which were handed out to crew and well-wishers on the shore for luck before the fleet embarked on a long trip. Boat’s biscuits are still available in the local family bakers of the East Neuk.

Fishing villages like Cellardyke were well served by a variety of specialist shops and trades (you would find quite the opposite if you walked through Cellardyke today).

Mary Murray remembers that not only were there bakeries but baker’s vans and milk was brought in on carts from landward farms even though Cellardyke had several milk factories.

It is hard to imagine how busy a place it must have been when the houses here were actually inhabited all year round often with several families crammed into one building.

Fruit, cakes and sweeties were seen as ‘treat’ foods, never consumed with the uncontrolled frequency with which we’re accustomed today. Food that we’d not consider as being particularly luxurious today such as steak pies and fruit loaves were regarded as celebratory fare for weddings and New Year for example.

If any older relatives couldn’t make it to the wedding the first plate dished out, called the “Bride’s Plate” would be carried round to them.

Though the lives of the fisherfolk in Fife were often blighted by tragedy, reading back through the oral histories of the people here, you can’t help but appreciate the closely-woven bonds amongst the community as well as the wholesome and largely seasonal and local fare on which it drew its strength.

Footsteps in the Furrow

Andrew Arbuckle’s Account of Fife’s Recent Agricultural History

Local journalist Andrew Arbuckle has been immersed in the world of agriculture for his whole life.

Raised in a farming family in North Fife, he went into business on his own account on land beside the mighty River Tay before concentrating on the worlds of journalism and politics.

He was the agricultural editor of the Dundee Courier for fifteen years, before going onto become rural affairs editor for the Scotsman.

Andrew has now written two books which reflect his own experiences together with some of the recent history of an industry which plays a key role in the local economy.

The title of the first book is “Footsteps in the Furrow”.

These excerpts from Footsteps in the Furrow by Andrew Arbuckle have been reproduced by kind permission of Old Pond Publishing, Dencora Business Centre, 36 White House Road, IpswichIP1 5LT. All rights reserved. www.oldpond.com

Chapter 11 – Soft Fruit

Chapter 12 – Sugar Beet

Work in the food industry?

Join the Food from Fife Community

Food from Fife is a membership organisation supported by Fife Council. It’s a way of bringing together one of the region’s most exciting and important industries with the aim of supporting it and growing the sector. As a Food From Fife member, you will have the opportunity to shape developments, meet and share experiences of other local businesses, get access to insights, training, marketing and trading opportunities and much more.

Keep Up To Date

Want something tasty in your inbox?

Find out all the latest news from Fife’s food and drink scene by signing up to our e-newsletter.

The food & drink community at the heart of Fife